Goldman equation

The Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz voltage equation, more commonly known as the Goldman equation is used in cell membrane physiology to determine the equilibrium potential across a cell's membrane taking into account all of the ions that are permeant through that membrane.

The discoverers of this are David E. Goldman of Columbia University, and the English Nobel laureates Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Bernard Katz.

Contents |

Equation for monovalent ions

The GHK voltage equation for  monovalent positive ionic species and

monovalent positive ionic species and  negative:

negative:

This results in the following if we consider a membrane separating two  -solutions:

-solutions:

It is "Nernst-like" but has a term for each permeant ion. The Nernst equation can be considered a special case of the Goldman equation for only one ion:

= The membrane potential (in volts, equivalent to joules per coulomb)

= The membrane potential (in volts, equivalent to joules per coulomb) = the permeability for that ion (in meters per second)

= the permeability for that ion (in meters per second)![[ion]_\mathrm{out}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/dc7e9cedbf6b51c90997a1108fa6251b.png) = the extracellular concentration of that ion (in moles per cubic meter, to match the other SI units)

= the extracellular concentration of that ion (in moles per cubic meter, to match the other SI units)![[ion]_\mathrm{in}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d4398d66174b0fca2224cd19631589bc.png) = the intracellular concentration of that ion (in moles per cubic meter)

= the intracellular concentration of that ion (in moles per cubic meter) = The ideal gas constant (joules per kelvin per mole)

= The ideal gas constant (joules per kelvin per mole) = The temperature in kelvins

= The temperature in kelvins = Faraday's constant (coulombs per mole)

= Faraday's constant (coulombs per mole)

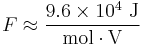

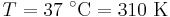

The first term, before the parenthesis, can be reduced to 61.5 mV for calculations at human body temperature (37 °C)

Note that the ionic charge determines the sign of the membrane potential contribution.

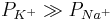

The usefulness of the GHK equation to electrophysiologists is that it allows one to calculate the predicted membrane potential for any set of specified permeabilities. For example, if one wanted to calculate the resting potential of a cell, they would use the values of ion permeability that are present at rest (e.g.  ). If one wanted to calculate the peak voltage of an action potential, one would simply substitute the permeabilities that are present at that time (e.g.

). If one wanted to calculate the peak voltage of an action potential, one would simply substitute the permeabilities that are present at that time (e.g.  ).

).

Calculating the first term

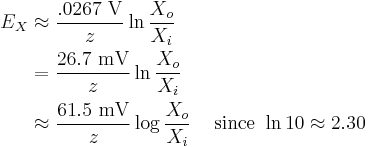

Using  ,

,  , (assuming body temperature)

, (assuming body temperature)  and the fact that one volt is equal to one joule of energy per coulomb of charge, the equation

and the fact that one volt is equal to one joule of energy per coulomb of charge, the equation

can be reduced to

Derivation

Goldman's equation seeks to determine the voltage Em across a membrane.[1] A Cartesian coordinate system is used to describe the system, with the z direction being perpendicular to the membrane. Assuming that the system is symmetrical in the x and y directions (around and along the axon, respectively), only the z direction need be considered; thus, the voltage Em is the integral of the z component of the electric field across the membrane.

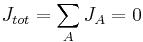

According to Goldman's model, only two factors influence the motion of ions across a permeable membrane: the average electric field and the difference in ionic concentration from one side of the membrane to the other. The electric field is assumed to be constant across the membrane, so that it can be set equal to Em/L, where L is the thickness of the membrane. For a given ion denoted A with valence nA, its flux jA—in other words, the number of ions crossing per time and per area of the membrane—is given by the formula

The first term corresponds to Fick's law of diffusion, which gives the flux due to diffusion down the concentration gradient, i.e., from high to low concentration. The constant DA is the diffusion constant of the ion A. The second term reflects the flux due to the electric field, which increases linearly with the electric field; this is a Stokes-Einstein relation applied to electrophoretic mobility. The constants here are the charge valence nA of the ion A (e.g., +1 for K+, +2 for Ca2+ and −1 for Cl−), the temperature T (in kelvins), the molar gas constant R, and the faraday F, which is the total charge of a mole of electrons.

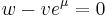

Using the mathematical technique of separation of variables, the equation may be separated

Integrating both sides from z=0 (inside the membrane) to z=L (outside the membrane) yields the solution

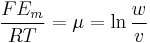

where μ is a dimensionless number

and PA is the ionic permeability, defined here as

The electric current density JA equals the charge qA of the ion multiplied by the flux jA

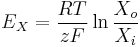

There is such a current associated with every type of ion that can cross the membrane. By assumption, at the Goldman voltage Em, the total current density is zero

If all the ions are monovalent—that is, if all the nA equal either +1 or -1—this equation can be written

whose solution is the Goldman equation

where

If divalent ions such as calcium are considered, terms such as e2μ appear, which is the square of eμ; in this case, the formula for the Goldman equation can be solved using the quadratic formula.

See also

- GHK current equation

- Nernst equation

- Hodgkin-Huxley model

- Saltatory conduction

- Bioelectronics

- Cable theory

- Morris-Lecar model

- Hindmarsh-Rose model

References

External links

- Nernst/Goldman Equation Simulator

- Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz Equation Calculator

- Nernst/Goldman interactive Java applet The membrane voltage is calculated interactively as the number of ions are changed between the inside and outside of the cell.

- Potential, Impedance, and Rectification in Membranes by Goldman (1949)

![E_{m} = \frac{RT}{F} \ln{ \left( \frac{ \sum_{i}^{N} P_{M^{%2B}_{i}}[M^{%2B}_{i}]_\mathrm{out} %2B \sum_{j}^{M} P_{A^{-}_{j}}[A^{-}_{j}]_\mathrm{in}}{ \sum_{i}^{N} P_{M^{%2B}_{i}}[M^{%2B}_{i}]_\mathrm{in} %2B \sum_{j}^{M} P_{A^{-}_{j}}[A^{-}_{j}]_\mathrm{out}} \right) }](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b484cb90615da3a7b33eef659f2da93e.png)

![E_{m, \mathrm{K}_{x}\mathrm{Na}_{1-x}\mathrm{Cl} } = \frac{RT}{F} \ln{ \left( \frac{ P_{Na^{%2B}}[Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{out} %2B P_{K^{%2B}}[K^{%2B}]_\mathrm{out} %2B P_{Cl^{-}}[Cl^{-}]_\mathrm{in} }{ P_{Na^{%2B}}[Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{in} %2B P_{K^{%2B}}[K^{%2B}]_{\mathrm{in}} %2B P_{Cl^{-}}[Cl^{-}]_\mathrm{out} } \right) }](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d4dc7bbb0c5a25dab4070ca6afd7a55e.png)

![E_{m,Na} = \frac{RT}{F} \ln{ \left( \frac{ P_{Na^{%2B}}[Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{out}}{ P_{Na^{%2B}}[Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{in}} \right) }=\frac{RT}{F} \ln{ \left( \frac{ [Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{out}}{ [Na^{%2B}]_\mathrm{in}} \right) }](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1d14ec033a7d1b5a3c914ddd27e6ee29.png)

![E_{X} = 61.5 \ \mathrm{mV} \log{ \left( \frac{ [X^{%2B}]_\mathrm{out}}{ [X^{%2B}]_\mathrm{in}} \right) } = -61.5 \ \mathrm{mV} \log{ \left( \frac{ [X^{-}]_\mathrm{out}}{ [X^{-}]_\mathrm{in}} \right) }](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fb268913a1210217aab6d93590bdd179.png)

![j_{\mathrm{A}} = -D_{\mathrm{A}}

\left( \frac{d\left[ \mathrm{A}\right]}{dz} - \frac{n_{\mathrm{A}}F}{RT} \frac{E_{m}}{L} \left[ \mathrm{A}\right] \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4c73f8dddc37993f5dee7456de854da6.png)

![\frac{d\left[ \mathrm{A}\right]}{-\frac{j_{\mathrm{A}}}{D_{\mathrm{A}}} %2B \frac{n_{\mathrm{A}}FE_{m}}{RTL} \left[ \mathrm{A}\right]} = dz](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8f2149509cc6c5981d541b1fbef6b3a8.png)

![j_{\mathrm{A}} = \mu n_{\mathrm{A}} P_{\mathrm{A}}

\frac{\left[ \mathrm{A}\right]_{\mathrm{out}} - \left[ \mathrm{A}\right]_{\mathrm{in}} e^{n_{}\mu} }{1 - e^{n_{}\mu }}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d1eea80a71dc3e014e1341efef3e49ba.png)

![w = \sum_{\mathrm{cations\ C}} P_{\mathrm{C}} \left[ \mathrm{C}^{%2B} \right]_{\mathrm{out}} %2B

\sum_{\mathrm{anions\ A}} P_{\mathrm{A}} \left[ \mathrm{A}^{-} \right]_{\mathrm{in}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/776f4653d08d25a395443f863c505759.png)

![v = \sum_{\mathrm{cations\ C}} P_{\mathrm{C}} \left[ \mathrm{C}^{%2B} \right]_{\mathrm{in}} %2B

\sum_{\mathrm{anions\ A}} P_{\mathrm{A}} \left[ \mathrm{A}^{-} \right]_{\mathrm{out}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d16281c7f03c86bbfcb343aebe8dab50.png)